Calisthenics and powerlifting feel like they’re on opposite ends of a strength spectrum. One has you using objects to move your body, while the other has you moving objects with your body. But at the core of it, both are a form of resistance training. Powerlifting is a barbell sport, but that doesn’t mean that calisthenics exercises are completely useless to a powerlifter. You can make calisthenics for powerlifting work quite well.

This is especially important when you’re stuck at home and don’t want to lose your gains. There are times when going to the gym isn’t feasible for financial reasons or other problems. Maybe you’re on a business trip and there aren’t any gyms around. Even a couple of weeks off can detrain you, so picking bodyweight movements to help keep your strength up can save your total from a long layoff.

Striking a Balance

An athlete who trains for speed won’t be as strong as someone who trains for strength. We specialize in what we need. We can also only train so many hours a day and handle so much training. Once we hit the limits of our work capacity, our training not only diminishes in quality, but we begin to waste time trying to half-ass two things instead of investing fully in one.

So, you choose how you train, and for powerlifters, the choice is clear: a bigger total, above all else. But that mentality might make us forget that just because an athlete in a different discipline trains a different way, does not mean that some of what they do doesn’t have a proper application in the long haul.

That’s where carryover comes into play – weighing the potential of an exercise based on how it ultimately benefits the end goal.

Powerlifters may lift for strength, but they need to do some basic conditioning to increase their overall work capacity, maintain a healthy cardiovascular system, and potentially reap the strength benefits of being able to train for longer periods of time.

Similarly, there are benefits to incorporating calisthenics into your powerlifting program. It’s all about exercise selection, and specificity – that is, picking exercises that best benefit you. And when you’re unable to pick up a barbell or head to the gym, calisthenics can be your best alternative to maintaining strength. Below are some of my favorite and most useful calisthenics for powerlifting.

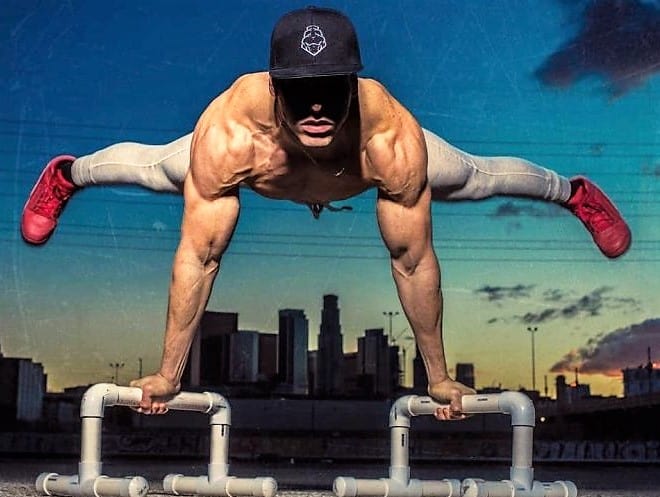

Pushups

Most people (myself included) probably stopped doing pushups once they discovered the bench. But the pushup is still a valuable tool if programmed correctly. Pushups are excellent prehab work to not only maintain healthy shoulders but for a number of miscellaneous upper body muscles that aren’t worked quite as much during the bench press, such as the intercostal and serratus muscles, and most importantly, the muscles surrounding your shoulder blades.

Pushups with resistance also double as an anti-extension ab exercise, and building a stronger, more flexible core with better diaphragm muscles lets you get a bigger belly breath for your bench.

It’s important to focus on quality when incorporating pushups into your training. Take advantage of the pushups differences versus a regular bench press. Because your shoulders are not meant to be fixed to the bench, they’re free to move around during the press. This gives pushups an advantage as a shoulder prehab and rehab exercise. You can further build on this advantage by adding instability into the mix, forcing the stabilizing muscles of the shoulder to work harder for each rep. Below are a few awesome pushups for powerlifters, especially those stuck at home:

- Regular pushups. You can do these with additional resistance (weights, bands, people sitting on your back) or with your hands and/or feet on elevation. You can also try different hand stances, with your hands closer together or further apart. The pushup is very versatile, but plenty of people do it wrong. Go through the full range of motion (chest hair touching the floor), keep a neutral neck, squeeze your quads and glutes and keep your core tight and spine neutral. Spread your shoulder blades apart at the top of the movement, and your scapular retract naturally at the bottom.

- Uneven pushups. These apply rotational forces to your torso, courtesy of gravity. By doing pushups with one hand on a different elevation, you can turn the pushup into a unilateral movement without resorting to one-arm pushups (if you lack the strength for them), and this makes your core work a little harder. Add resistance, or go one-armed, or add resistance while one-armed.

- Unstable pushups. You can do these with a basketball, or two basketballs, or rings, or plates (pinch them and do pushups while balancing on the edge of the plates) or bands (attach the bands to two parallel bars and do “earthquake pushups”). You can get really creative with these. Anything that isn’t a stable surface can work.

Pullups

Pullups are almost mandatory in every training program. While I wouldn’t say they’re the king of upper body exercises in every discipline, pullups are a very good way to build a stronger, bigger back, and they’re easy to program and progress in. All you need a pullup bar, and any kind of sling bag, dip belt, backpack, or heavy vest.

If you’ve got a sturdy table, slow table rows are a great way to train a horizontal row, and resistance bands can either make pullups easier or give you an option for single-arm rows and lat pulldowns. Below are a couple of my favorite calisthenic pulling exercises, for when you can’t use a gym:

- Pull-Ups. They’re incredibly versatile. Start with a grip you’re comfortable with, and do negatives until you can do a single solid rep. If you have resistance bands, slinging them around the bar and onto your knee or foot will take some weight off the lift, making it easier. You can also use bags and vests to make pullups harder or work towards a one-arm pull. For a different kind of challenge, pull yourself into a muscle-up from a dead hang without completing the muscle-up – just touch the bar with your lower abs, and repeat.

- Table rows. Any sturdy table will do, as will a low hanging bar. These are simple rows with your feet on the ground. Aim to pull yourself up so you’re pulling your lower chest into the bar/edge of the table, rather than your neck. This is to make sure you’re targeting the lats better.

- Lever raises. These are an inverse bodyweight lat pushdown. From a dead hang, you’ll want to engage your core, keep your toes pointed and legs straight, and aim to use your lats to pull your body into a front lever, basically getting parallel to the ground. Awesome core and lat exercise without as much bicep engagement as the other two.

Ab Work

The most impressive ab work is usually the stuff you see “street workout” dudes do. Front levers, back levers, flags and planks are by far the best way to build an unbelievably sturdy core. Throw in a few flexion and twisting moves, like windshield wipers, raises, and Russian twists, and you’ve got yourself a comprehensive ab routine using nothing but the bar and the floor.

Impressive doesn’t always mean effective, but there are plenty of gems in there. Many of the really effective ab exercises are calisthenics exercises (save for heavy cable crunches and farmer carries), so this one is a no-brainer. Ab calisthenics work for powerlifting with seamless integration. Here are a couple I’d do at home:

- Planks. You can do these with weight, on your elbows, on your hands, on your side, with your legs or hands elevated, with your hands and feet much further apart (bringing yourself closer to the floor), and so on. I don’t recommend doing these for time. I don’t see much of a point in holding a plank for longer than 30 seconds. Aim to contract and squeeze your torso, glutes, legs, and arms as hard as possible (without spinal flexion) during any given plank, and use different progressions to challenge yourself.

- Front levers. These are quite challenging, so you can begin by doing negatives, or by doing tucked front levers (with your knees to your chest. Front levers require a pullup bar and quite a lot of strength. Start from a dead hang and use your lats to pull your body into parallel with the floor. If you can’t hold this position, straddle your legs (keep them as far apart as you can) to shorten the lever. You can shorten the lever further by tucking your legs in. The further you tuck them in, the easier the hold. Start with ten seconds per set, and aim for a full minute (six sets to begin with), and progress when you can do two sets of half a minute.

- Heavy holds. Calisthenics exercises don’t typically use any weights, but this is something you can do at home with little trouble. Just find any one object you can pick up and hold in one arm with a comfortable grip (a propane tank, a 4-gallon jug with a handle, a suitcase), make sure it’s appropriately heavy, and hold it in one arm for time. Focus on staying perfectly upright. If you’ve got the space, go for a walk.

Dips

Dips are an awesome tricep exercise. The bodyweight dip is the pushing equivalent of the pullup, yet I don’t see as many people rave about it. That’s probably because lots of beginner lifters find dips to be too harsh on the shoulders, and that can be true.

If performed incorrectly or with not enough mobility/flexibility, you may find dips uncomfortable. When it comes to what works best in calisthenics for powerlifting, the upper body dip is on-par with the pullup as the best no-weight accessory.

And even if you can easily perform bodyweight dips, there is an upper limit to the exercise. At some point, you’ll reach a level where strapping more weight onto yourself is just not a good idea for your shoulder joint, even if you can realistically press far more.

This is why I see dips as an ideal hypertrophy exercise, although it’s fun to push yourself and see if you can do dips with two, three, or even four plates. You’ll want to have strong shoulders if you attempt heavy dips – but they’ll also contribute to that, by strengthening your anterior deltoid. There’s not much to be said here: you can do these weighted or with a band if you want a slower, lighter descent. Other variations detract from the main point of the dip – pushing power – by incorporating the legs to do more core work.

Squat Alternatives

Most people think that calisthenics doesn’t have very many options for leg development, but with a little creativity, you’ll find that that isn’t necessarily true. There are a few squat variations that will pass as calisthenics for powerlifting when using the appropriate resistance.

For example, you can go for pistol squats, split squats with a heavy object, goblet or back squats with water jugs or sacks of cement/heavy bags/front-loaded backpacks, or sissy squats (don’t do these if you’ve experienced a knee injury). Resistance bands will do a lot to greatly improve your workouts, and you can load these any which way, doing banded front squats, back squats, split squats, and lunges. You can even pick up a person and use them to make your squats harder. Ask for permission first, though. Here are my top choices for squat alternatives:

- Single-leg squats. If you’re tired and bored of bodyweight squats, and can probably do a hundred or more before you start getting tired, it’s time to graduate to something else. Single-leg squat progression starts with an elevated surface. Keep one foot on the elevated surface, which can be a shoebox or a small stool or step, and just squat down until your other leg touches the floor. Get a higher surface, and repeat. If you have trouble holding the bottom position due to ankle mobility, try squat shoes or use weight as a counterbalance. You can also start with lunges or split squats.

- Jump squats. You can one-and-one-half these. Instead of going into a deep squat, jumping explosively out of the hole, and immediately burying yourself into another deep squat, absorb the impact of the jump with a quarter squat. You want to land softly, and use the jump squat to really go for maximum power out of each jump, rather than trying to turn it into a cardio exercise. Do sets of 5-10, and use variations like tuck jumps or box jumps to make the most of the exercise.

- Sissy squats. These are incredibly hard, not because they’re hard to do, but because they’re hard to do safely. If you have strong legs, are sufficiently warmed up, and understand how the exercise is performed, it can be an amazing quad isolation exercise. It can also easily cause a beginner to sprain a knee ligament and experience mild pain for months. Take care to do these right. Start by using a table or doorframe for assistance, and focus on keeping your hips and torso completely extended and straight – only your knees should flex.

Hamstring and Glute Exercises

We can’t forget about the posterior chain! Most people think of their quads when they want to build strength and size in the lower body, but your posterior chain is critical not only in the squat, but in the deadlift as well.

You’ll want strong glutes, strong hamstrings, and strong hip flexors, especially if you want to avoid detraining too much while out of the gym. There are plenty of glute bridge variations, as well as hamstring exercises (yes, really!) and adductor/abductor movements. You’ll need to get pretty creative with these and might need a few things, so bear with me. Here are my top three.

- Glute bridges. You can do these with both legs, single-legged, with bands, with your torso on an elevated surface, with weights, and so on. They’re rather simple – be explosive, hold the contraction, and maximally extend your hips. That last cue is the most important one.

- Ham curls. For these, you’ll need some furniture sliders, or soft socks on a slippery floor, or an exercise ball. Simply place them under your feet, keep your torso and hips extended, and curl those hams. You can also ask help from another person to perform Nordic ham curls.

- Hip hinges. Hip hinges are deadlifts, good mornings, and similar movements. Single-legged hip hinges (Romanian deadlifts on one leg) act as a great deadlift accessory, at home, and at the gym. Use dumbbells, barbells, kettlebells, water gallons, or anything heavy to perform this exercise. Good mornings are also an excellent at-home alternative to deadlifts, forcing you to brace properly.

Calisthenics Aren’t Lifts

It might be painfully obvious, but yes, calisthenics work is never meant to outclass or replace an actual lift that you’re training for. Calisthenics is never going to be on par with primary and secondary lifts. You can make calisthenics work for powerlifting, but you still need to lift. If that isn’t possible, I should stress that you can still build strength and muscle with a calisthenics program.

Some of these exercises are really hard. They will make you stronger. But it isn’t the kind of strength that will directly translate to a bigger total. When taking a long break from the gym, expect to lose some proficiency with each of the three major lifts, and reduce your maxes by 10-20 percent, based on how long you’ve been gone. However, you can still maintain muscle mass and work on weaknesses or imbalances during your time performing calisthenics for powerlifting.

To understand how exercise selection works when building a powerlifting program, it’s important to know how exercise tiering works. A program will always constitute of tier 1, 2, and 3 exercises. The different tiers represent the primary movement for a particular training goal, a secondary lift to increase volume in a particular movement, increase muscle mass or overcome a sticking point, and finally, accessories that act as prehab/rehab, or as “powerbuilding” work. As an example:

- Tier 1: Primary lifts and variations thereof that you can train within the 85-100% 1RM range. This includes your big three, but it also includes variations such as high-bar versus low-bar squats, sumo versus conventional deadlifts, paused (competition) bench versus touch-and-go.

- Tier 2: This includes other variations usually performed in the 70-85% 1RM range. This can also include your alternative deadlift (sumo if you pull conventional, and vice versa), deficit or banded deadlifts, floor pressing, overhead pressing, close grip press, incline press, paused squats, front squats, heavy split squats, and more.

- Tier 3: This includes exercises meant to help you improve on your Tier 2 exercises, and target weaknesses that you may have, or increase size. Machine exercises, from leg presses to extensions or curls, pullups, rows, lat pulldowns, dips, and more – these all fit in Tier 3.

Calisthenics in Tier 3

Exercises are tiered this way based on their relevance towards your ultimate goal: a bigger bench, deadlift, and squat. Tier 1 exercises are meant to immediately carry over to a bigger bench, deadlift, or squat. As such, your primary Tier 1 exercises are going to be the bench, deadlift, and squat. Tier 2 is meant to help you improve upon Tier 1 exercises, while Tier 3 can be isolation work to get past sticking points in Tier 1 and 2.

Calisthenics for powerlifting can be excellent for mostly Tier 3 work, but it’s not meant to replace Tier 1 or 2. Some argue that dips and weighted are the greatest chest builders out there, but your T1 and T2 exercises for the competition bench press should still revolve around the press and its many different variations. Others say that you can build a powerful back doing tons of pullup variations, but pullups are nothing more than a way to keep the back healthy and improve on your strength for the pull, press, and squat.

As a powerlifter, you need to prioritize your exercises accordingly but always keep an eye out on the usefulness of incorporating different movements into your training to test them for potential carryover.

Athleticism – that is, speed and power generation – might not traditionally have much to do with static force production, but learning to be explosive out of the hole can help you generate the sort of speed needed to shoot past a sticking point.

In the same way, however, taking the focus off your T1 and T2 lifts too much can be detrimental to your progress, and can even send you losing gains. Calisthenics for powerlifting can help you shore up weaknesses, stay strong outside of the gym, and maybe pick up interest in a new kind of strength. But it won’t replace a barbell.

The Bottom Line

Should you train the competition squat, or use a variety of squats? In both theory and practice, both are viable ways to improve. No matter how you slice or dice it, if you train your legs a lot and squat often, you’ll build the muscle size and the necessary neural pathways to execute an efficient, proficient squat for your size and training age.

Some individuals respond better to training almost solely the squat, while others might benefit from expanding their training and tiering their exercises. That depends on how far along you are with your training, and what you best respond to both physically and psychologically. Sometimes what you need isn’t more raw strength, but a consistent technique. At other times, it takes more than just muscle stimulus to keep you training – getting bored can make you stall or stop lifting.

Calisthenics for powerlifting can be a nice change of pace and help you further pad out your exercise roster, and swap some of your accessories for something different, like a pushup variation or single-leg squats for joint stability.

If you want a simple bodyweight program with a few weighted options/dumbbell exercises thrown in to help you stay strong, give my home program a try, and let me know below if you’ve got go-to bodyweight exercises.