The pushup is the quintessential resistance exercise. Perhaps not in terms of effectiveness, but certainly in terms of reputation. It’s a dead-simple exercise and can be done on the fly, like many other calisthenics movements. But its simplicity doesn’t diminish its usefulness. While many powerlifting beginners tend to neglect their pushups once they discover the barbell, I’d argue we need more pushups in powerlifting programming. It isn’t just a conditioning exercise.

When performed properly, the pushup is an incredibly versatile movement that acts in perfect harmony with the bench press.

Many people don’t know how to do a proper, consistent pushup. Since I see the same problem with pullups, I feel like I should call it the calisthenics problem – but it’s honestly just an exercise problem.

People get lazy when they need to do the same thing over and over again, and while we powerlifters get anal about proper form in the bench press, squat, and deadlift, it’s easy to turn a blind eye to a bad pushup.

Pushups and other cheap and easy pressing exercises are especially important now, as most gyms around the world are closed or closing due to the current pandemic. While we’re unlikely to see something on this scale again any time soon, home workouts will still have their place whenever the gym just isn’t an option. And the pushup, while not a one-to-one twin of the bench press, is a great complementary exercise.

Why Bother with Pushups?

There are plenty of reasons to bother with pushups, including the fact that they’re the easiest way to do triceps and chest work, they’re the one bodyweight movement that most closely mimics the bench press, and they can be done anywhere, at any given time, on even floors, uneven floors, objects, beds, tables, and so on. But perhaps the single most compelling reason to do pushups for powerlifting is the benefit of shoulder stabilization.

A pushup is very different from a bench press. I do write that pushups closely mimic the bench, but they’re far from the same thing. The movement is completely different, especially in the shoulders and torso. The arch in the spine is gone in a pushup. The range of motion is different.

The pushup is still an excellent supplementary exercise for the bench press because it allows the scapulae (shoulder blades) to move freely throughout the lift. Pressing exercises, whether with a barbell, a dumbbell, or anything else that’s weighted, typically do not allow for the free movement of the scapulae.

When you’re doing pushups, you’re pressing yourself up off the floor, rather than lying down and fixing your shoulders into a stable position to safely press weight off your body. The natural retraction of the shoulders at the bottom of the movement and protraction at the top allows you to utilize a greater range of important stabilizing muscles that help keep the tendons of the shoulder joint safe.

Let’s remember that the shoulder joint is a complex, important, and incredibly fragile ball-and-socket joint with extreme mobility (far more than any other joint in the human body), and many little ligaments. The various muscles that intertwine with the shoulder joint are necessary to keep it safe, and the pushup does a great job of targeting these smaller muscles, especially through challenging variations that demand greater stability.

The pushup is also easily modifiable through resistance bands, or weights, with a little help. You can also try different variations of the exercise to better target one of the three primary movers (the triceps, the pecs, and the shoulders) or go off the deep end entirely, and take your newfound love of the pushup to greater heights with gymnastic variations.

The Anatomy of a Proper Pushup

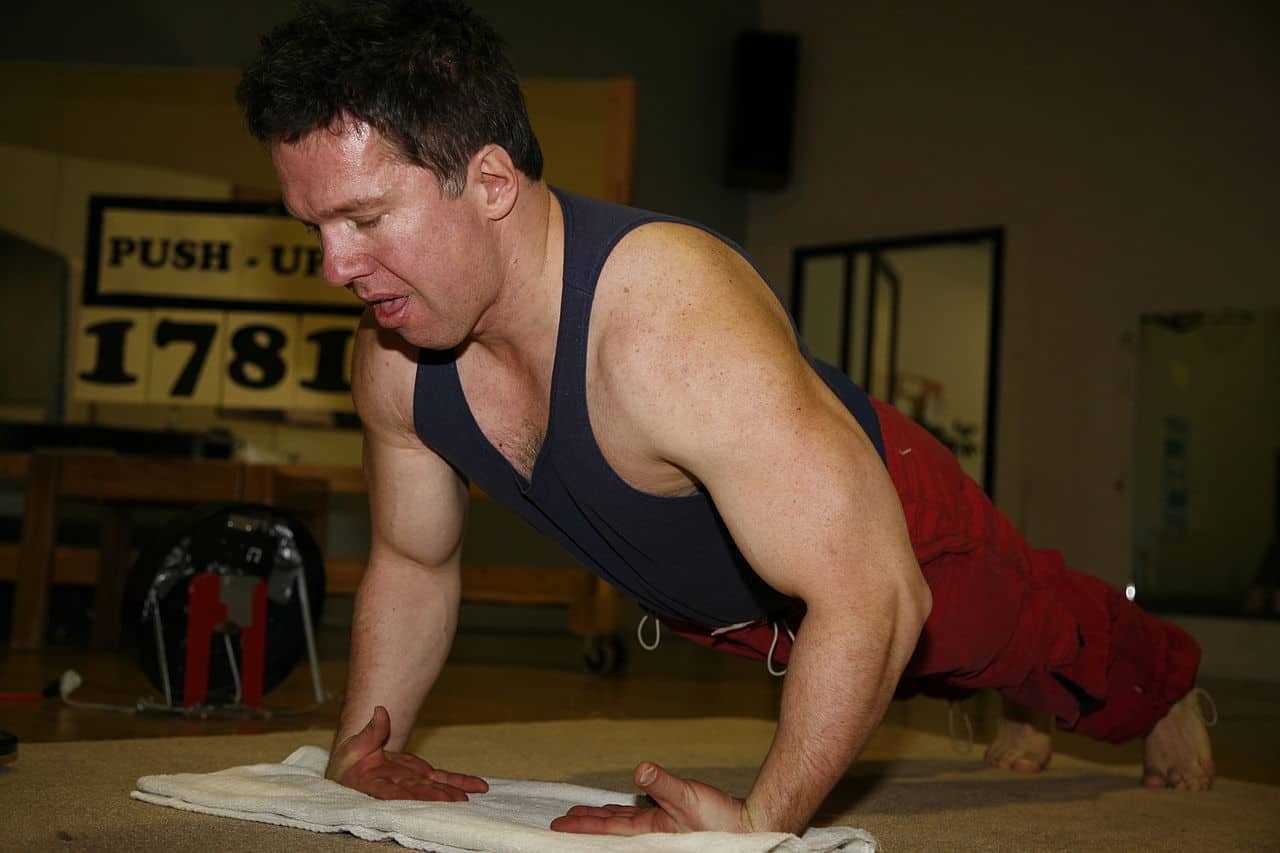

If we want to make the most of this exercise, we need to do it right. There’s not too much to it, thankfully. Hand stance and such doesn’t matter and can be changed to suit your specific preferences. You can do pushups with your hands far apart, or close together, or with just one arm. If you want the most balanced approach – one that taxes the arms and chest alike, and makes the most use of your body’s natural pushing mechanics – then keep your hands about shoulder-width apart plus an extra hand-width, with your elbows at a 45-degree angle from your torso.

Next, the top position. A proper pushup starts in a plank. To do this correctly, brace your core and tighten your glutes. The idea is to keep a stiff and neutral spine, with no slack through the stomach. Push through into your toes and keep your quads extended, so your legs are straight. Keep your neck neutral – not up, now down. From a side view, you should be able to cleanly trace almost a perfectly straight line from your heels to your neck.

From there, you start the pushup. Bring yourself down until your chest touches the floor and explode – with maximal effort – back into the starting position. Maintain the tightness I’ve described above throughout the movement, focusing only on spreading the ground below you with your arms as you lower yourself, and pushing yourself as far away from the ground as possible in the concentric phase. Finish each rep with protracted shoulders, meaning, try to engage your shoulders to push yourself as far off the ground as possible. You should feel your shoulder blades spread when you do that. That’s the right sensation.

Rinse and repeat. Of course, while I say that most people probably have no problem doing a proper pushup if they’ve been powerlifting for a while, that isn’t always necessarily true. Some people, especially after shoulder injuries, or given a certain bodyweight, will struggle with a pushup even if they’re quite strong in the bench. They’re not the same thing.

Neural adaptations for the bench press don’t translate very well into the pushup, either. But if the regular pushup is a little too easy for you, there are plenty of ways to gear pushups for powerlifting and make them much tougher.

Making the Pushup Harder

There are a couple general tips for making the pushup harder. These include:

- A variation in setup. Examples include diamond pushups, single-armed pushups, clapping pushups, dive-bomber pushups, and Spider-Man pushups.

- Added resistance. These are banded pushups and weighted pushups.

- Added instability. These include doing pushups on round or unstable objects, from sports balls to exercise balls, rings, TRX setups, resistance bands on parallel bars, and so on.

However, of all of these variations, which are actually effective pushups for powerlifting? That depends entirely on what it is that you’re trying to achieve. When incorporating pushups for powerlifting, it’s important to single out what it is that you want your pushups to contribute to your program. If you’re doing them to avoid detraining at home, you’ll want to do program them in a way that emphasizes either hypertrophy in important muscle groups or challenges your pressing skills. Here are my favorite pushup variations:

- Diamond pushups. These are just close-grip pushups, and they’re ideal for triceps hypertrophy. I like to knock out a set or two between exercises when I need to do a bodyweight session, and they’re still useful as an alternative to other triceps accessories when at the gym. You can easily make these harder with bands or weight, but don’t try to go for strength. You’re just trying to get as many quality sets of 10-15 reps as you can.

- Heavy banded pushups. The closest thing to the bench press that you’re going to get without a barbell or dumbbells of some sort. The idea here is really simple. Wrap the band behind your back with one end in each hand and do regular pushups. Add more bands or bands with more resistance once it gets too easy. You can use a set of bands to program progressive overload and work towards a seriously heavy pushup. Figure out resistances that let you crank out sets of 8, sets of 5, and sets of 3. Work up to 12, 8, and 5, then go up one level of resistance. Repeat.

- Ring/TRX pushups. Do these with a supinated or neutral grip if a pronated grip is uncomfortable. The idea here is to use the instability in combination with a slow and controlled eccentric to really tax your shoulder stability. These aren’t hard because they’re increasing the resistance, but because you’re so much less stable than on solid ground. Great for shoulder rehab/prehab.

- One-armed pushups. These are only useful if you’re strong and light enough to do any meaningful amount of work with them. Lifters in lower weight classes will usually be able to crank out way more of these. Their main purpose is as a unilateral exercise to work on patching up weaknesses and addressing inconsistencies. If you’re significantly stronger in one side versus the other, that won’t just be a matter of strength, but it may be a matter of stability or technique. Work towards doing the same reps on one arm as on the other (or close to the same reps).

Other variations are interesting, to be sure, but not very powerlifting-specific. For example, if you want to work your chest, then standard banded pushups or weighted pushups are your best bet. They’re better than cutting your range of motion shorter with a too-wide grip. Other pushups often just detract from the purpose of the pushup as an auxiliary exercise to the bench press.

Handstand Pushups

I’m addressing handstand pushups separately because while they’re a bodyweight pressing exercise, they’re very different from a regular pushup. I’d argue that there isn’t much of a point in doing handstand pushups if you’re at a gym with access to a barbell, as it’s essentially the same movement but upside down so that you’re the load.

There’s certainly a much higher stability demand, especially if you’re doing them “freestyle” (not leaning against a wall). Otherwise, the same rules apply as with a barbell. Tight core, tight glutes, and go.

If you’re not strong enough to start from a wall handstand position, start with pike pushups. You can do these with your feet elevated on a chair, and your torso angled perpendicularly to the ground. The next step would be to work on eccentrics against the wall, until you can complete a solid rep. The next level is to work on a handstand away from the wall, and eventually do full handstand pushups with your hands on an elevated surface (parallettes, usually).

Dips for Powerlifting

Dips are even better at building strong triceps than diamond pushups are, but their biggest disadvantage is that you need access to parallel bars to pull them off. You can use chairs, but they should be seriously sturdy. If you can do dips, then, by all means, do them.

They allow you to go through an even greater range of motion for the shoulders and triceps than pushups typically do, and slow eccentric dips are a good test of shoulder health. Just remember to keep your shoulder blades retracted and avoid swinging.

Balance Presses with Pulls

No matter how many powerlifting pushups you’re incorporating into your programming, remember to balance these out with pulls. Table pulls, pullups and rows with heavy household objects are all excellent choices, and if you’ve got bands of any kind, you can fix these to a hook or post and do single-arm pulls, scapular retraction, and face pulls.

In powerlifting, pushups can be a great tool to keep your shoulders healthy by going through the full and natural range of motion of a push every now and again. Various kinds of pushups also do an excellent job of keeping you from completely losing your pressing power over the weeks and months you might have to spend without a gym. What pushup variations do you like doing?