Front squats are a tougher variation of the back squat, with the barbell held in a “front rack” position resting on the lifter’s anterior deltoids. However, for many lifters, it isn’t quite clear why the front squat is tougher.

Some presume that it’s the fact that the front rack demands much more of a lifter’s shoulders, causing them not to lift as powerfully as they otherwise might. Others think it is because the front squat causes an inefficient distribution of force through the quads and hips because of a more upright torso angle, so the quads are taxed more heavily than in the back squat, and the lifter can’t lift as much. Others yet propose it’s because front squats are more taxing on the abdominal muscles.

The real reason why the front squat is a tougher lift than the back squat, and a valuable lift in the arsenal of any ambitious powerlifter, has to do with bar positioning and how it affects the mechanics of the squat, as well as the difficulty of the front rack position for many beginners.

Front Squats Vs. Back Squats

Front squats, low-bar back squats, and high-bar back squats are the three major squat variations that dominate the sports of powerlifting and weightlifting. Weightlifters use back squats to train their legs maximally, and front squats to train a specific portion of the clean and jerk, one of the two major movements in the sport. Powerlifters add the low-bar squat to the mix, often adding as much as 10 percent extra weight onto the bar by simply shifting the bar onto the lower traps.

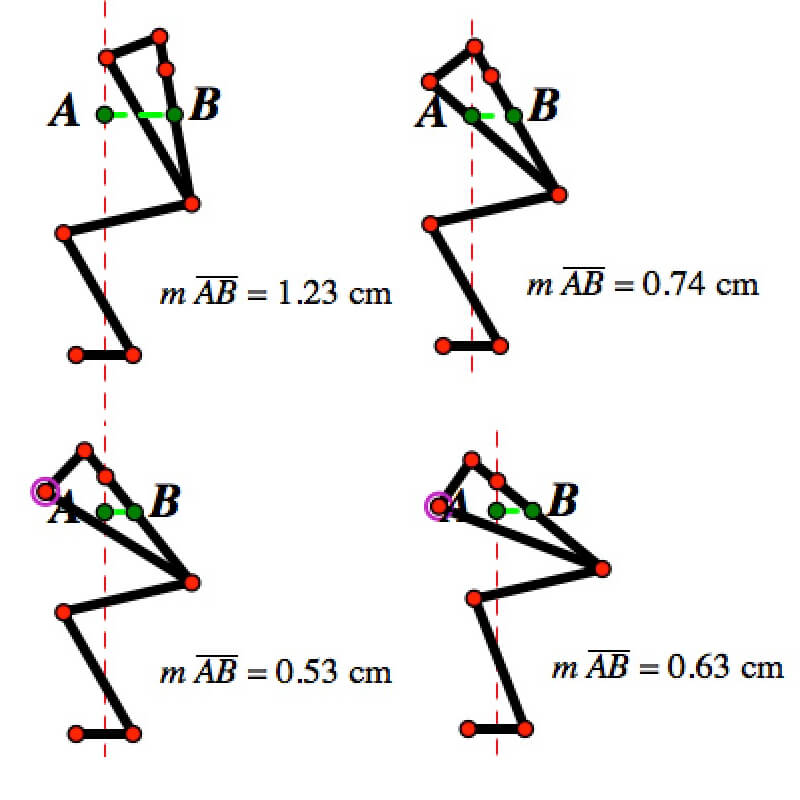

Each of these lifts is unique because of where the bar is placed on the body. An efficient squat is a balancing act wherein the bar must constantly remain within a perfectly straight bar path from the top of the movement, down to the bottom, and back. This bar path is angled right above the midfoot, such that a lifter can press maximally through the entirety of the foot, and not just the heel or the ball of the foot.

As such, a lifter’s torso angle, knee flexion, and hip flexion will differ depending on:

- Bar position.

- Torso length.

- Femur (thigh) length.

- Tibial (shin) length.

- Ankle mobility.

- Foot stance.

While these factors all cause people’s squats to look wildly different, the following can generally be assumed:

- In a front squat, the hips are flexed the least, while the knees are flexed the most. Most people front squat less than they back squat, assuming they train both.

- In a high-bar back squat, hips and knees can be flexed more or less depending on the lifter’s strengths and preferences. Most people back squat more than they front squat.

- In a low-bar back squat, the hips are flexed the most, and the knees are flexed the least, although knee flexion is still important in order to break parallel. Most people lift even more with a low-bar position versus a high-bar position, which is why it’s popular in powerlifting.

With this information in mind, you might assume that the biggest difference here is how the front squat forces more knee flexion and less hip flexion, and hips are stronger than quads. Therefore, front squats are harder because they tax the quads more. Right?

Wrong. While your hips are indeed usually stronger than your quads, squats are not truly hip-dominant nor quad-dominant. Positionally, a squat can be more or less reliant on hip flexion or knee flexion based on bar position, but your hamstrings and glutes actually work really hard to distribute the load across your quads and hips relatively equally, or more accurately, they’ll work to ensure that your hips and quads do their best in any kind of squat. You can still have weak quads or weak hips relatively-speaking, but that doesn’t account for the big difference between the front squats and back squats.

Knee and Hip Flexion in the Squat

A squat is initiated with knee and hip flexion – you descend and bend at both the knees and hips in order to go into a full squat and extend both in order to return to a standing position. This is why your primary movers in the squat are, ostensibly, the quads and glutes. Your adductors also work surprisingly hard in a squat, much more so than your hamstrings.

In fact, your hamstrings don’t do as much as you’d think they do. That soreness in the back of your thigh after a heavy squat day comes from your adductors. They work with your glutes to extend the hips, while the quads work to extend the knee. Your hamstrings and one of your quad muscles, the rector femoris, work to help transmit force throughout the musculature of your lower body, so a squat is never full hip nor quad dominant, especially if it’s a heavy squat.

Your body will naturally rely on your quads to extend the knees, and your hips will shift back naturally once your quads tire out to help push through the sticking point (above parallel) before the knees shoot back forward and the hips shoot under the torso to get upright. Watch any weightlifter attempt a max back squat and watch as their torso angle shifts towards the sticking point, and then immediately shoots back into an upright position.

Lifters can’t afford for this to happen in the front squat. And this, in particular, is interesting. It hints at the real sticking point in the front squat: your erectors.

Greg Nuckols pointed out in one of his articles that, as your torso and limb angles change from squat to squat, so too does the demand on the thoracic extensors. In the front squat, the upright angle of the torso would superficially imply that spinal extension demands are low – but because the bar is so much further away from the hips and spine, the moment arm between the extension muscles in your upper back and the path of the barbell is massively longer in the front squat than it is in either one of the back squats.

This, combined with the fact that a lifter cannot afford for their torso angle to change significantly during the front squat, meaning they cannot maximally load the legs and hips, makes the front squat much harder – especially if you try to lift the same weight, or have a weak back. But what does this mean in practical terms? It means that:

- The front squat is not optimal for quad development. Even though it demands greater knee flexion than a low-bar squat, it also requires a significantly lighter load, up to 20% lighter for most people. You’re better off high-bar squatting.

- The front squat is an awesome upper back exercise. It’s especially great if you have thoracic extension issues, i.e. your upper back rounds in the deadlift or limits your back squat. Front squats are also a great complementary exercise for back squats and deadlifts, especially conventional deadlifts.

There’s another big reason why the front squat is so much harder than the back squat, it’s because it requires much greater upper body and lower body mobility.

The Front Rack vs. the Back Rack

The bar position in the back squat is quite simple – squeeze your upper back, grip the bar as closely as you can depending on your shoulder mobility, and angle your elbows either down or back in order to create a thick shelf of contracted muscle for the bar to sit on throughout the lift. It still takes practice, and far too many lifters carry the bar on their back without enough tension, which is part of why their balance shifts in the lift, and why they might experience spinal rounding (bracing is also a problem here).

However, the front rack is a far more demanding position. A good front rack requires that a lifter keeps their elbows high throughout the lift, while the torso remains upright. A lifter’s upper arm should be about parallel to the floor throughout the lift, except at the sticking point, where it shifts a little bit lower as the torso becomes less upright.

In order to achieve a good front rack, lifters need a combination of strength, mobility, and practice. The wrists, shoulders, and back must be flexible. They must learn to externally rotate their shoulders and raise and protract their shoulder blades. Because it’s a completely different kind of racking position, lifters need to train their bracing in the front rack as well as in the back rack and understand that both feel very different. They also need to warm up.

The demands on the core are not greater in the front squat than they are in the back squat – in fact, the heavier load in the back squat makes it much more challenging for the core – but most lifters just don’t know how to properly brace for the front squat because they don’t front squat as often. If you’re having trouble getting a good front rack, try these tips:

- Get weight on the bar, or use a smith machine, and just stretch into a front rack without unracking the weight yet.

- Drive your elbows under and over the bar and adjust your shoulder blades to get your elbows to point forward and up.

- Try to think of slightly squeezing your elbows together while keeping your hands further out on the bar. This will help you stretch your shoulders’ external rotation. Try to think about making your triceps face each other.

- Unrack and hold the bar once you’re more comfortable with your elbow and shoulder position. Once you can get a solid front rack, you can start working on maintaining that form as you squat.

- If you’re caving forward in the front squat, work on getting your hips under the bar and keeping your elbows high. If you have trouble with getting your hips under you, you might have ankle mobility issues. Squat shoes and ankle mobility drills before squatting will help.

Remember – elbows forward and up, shoulders rotated externally, shoulder blades protracted and raised, and upper back kept “tall”.

Front Squats are Limited by Thoracic Strength

Flexibility and improper cueing aside, thoracic strength is the natural limiter in the front squat. Even with a perfect front squat, you won’t put as much weight in your front rack as you would in your back squat if you train both often, even if you front squat or hold weight in a front rack considerably more often (as weightlifters often do).

This is a good thing because working on that thoracic extension will help you develop a stronger and more stable deadlift, and even eventually help you intentionally flex and extend the t-spine in max attempt deadlifts to reduce that range of motion from the floor (i.e. intentional upper back rounding in the deadlift).